Monday, February 9, 2026

Monday, December 8, 2025

Hey there.

Is it just me or has remembering to celebrate the good things felt increasingly more exhausting? Because there are good things, but often they either go unsaid or immediately vanish under the weight of everything else. Every time I decide to point out something cheerful, I immediately come across fifteen deeply bad events that make my cherry pie/funny coat/passing fox/new snow feel as wrong to mention as it is to toss peanuts into an open coffin during a funeral.

(You know, I recently had a therapy appointment in which I told a story about a situation where someone was unexpectedly away and I kept changing the date I promised everyone they’d return. I’m pretty sure they’re going to assume I murdered the person and am trying to cover it up, I told my therapist. She laughed and said she was surprised I went there. And I was surprised that after so many years she didn’t know that I not only went there, I lived there. Small One and I still giggle about the time we drove around with a tarp, a box of latex gloves, an old rug, an set of battered license plates, and a bag of zip ties in the trunk. Every item had its own separate reason for being there–art students and experimenters travel with odd baggage–but it made for a sketchy still life.

Or there was the time the gutter people were out to fix the gutters, and they were going up and down a ladder in front of the kitchen window, and there on the kitchen counter was a sizable quantity of white powder, a scale, and a ten inch serrated knife. Confectioner’s sugar, my friends, for the icing on a cake, a scale to accurately measure the cake’s ingredients, and a knife for the bread I had yet to cut, but. Yes, I wondered whether the gutter people were thinking she’s a respectable gray-haired lady cleaning the oven and drinking a cup of tea, but also, is she going to kill us now that we’ve looked in the window? Of course I was not going to kill them. It was broad daylight and there were two of them and the solar installation folks were going to be arriving shortly.

All of which is to say, I apologize if throwing peanuts in an open coffin during a funeral is in bad taste. It’s just the first thing that sprang to mind.)

In case it isn’t already painfully clear, I do have a bit of good news. I’m going to tell it to you, regardless of the despair in the air, because if a book has a good thing happen and the author never mentions it anywhere, that good thing reverts to the equivalent of a blank stretch of wall where a picture was meant to go, only no one bothered to drive the nail in and hang it up.

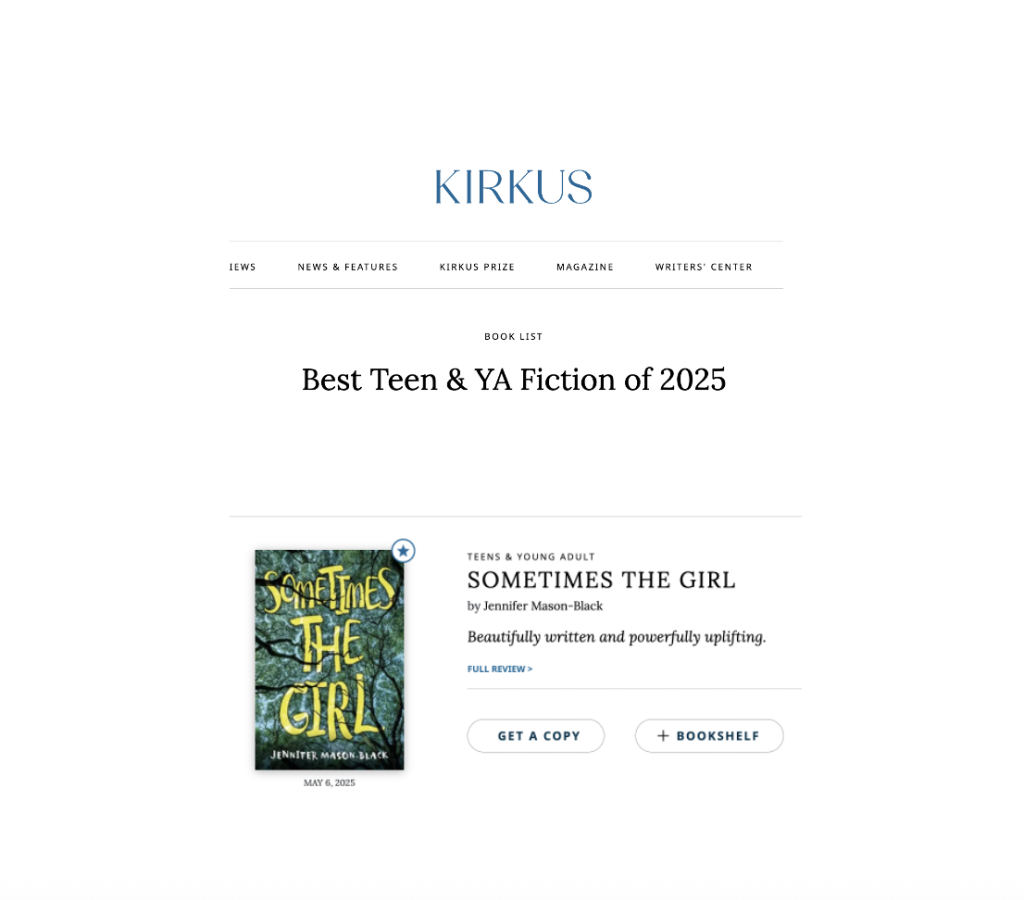

As I mentioned elsewhere, this is not exactly how the list looks. It’s just hard to take a picture of eleven books that is neither huge nor so small it might as well be a map inside a toy car. I can promise you that it is a list of brilliant and beautiful books and I’m thrilled Holi’s story is among them. You can check it out here.

That’s all I have to offer today. If you’ve stumbled onto this post and wonder why there aren’t many more, subscribe here! It’s free, it’s painless, and it will give me a welcome break from denying membership to bots. Also, the majority of the posts are behind the not-paywall. There, I occasionally talk about things I’m working on, like Jen’s Big Book of Apocalyptic Nightmares. Trust me, it’s more disturbing than it sounds. Though Sometimes the Girl was once The Encyclopedia of Trauma and people don’t tend to come away from it scarred. Perhaps all my working titles should just be Another Volume of Hyperbole.

Until we meet again, Dear Ones.

Tuesday, November 25, 2025

Tuesday, November 4, 2025

October 27, 2025

News Roundup for Sometimes the Girl, May 2025

Hey there!

I’ve got a compiled list of places Sometimes the Girl has shown up of late. For subscribers, some of this may be a repeat. And those of you who are not subscribers, join us! It’s free and easy! Better yet, I’ll be doing some deep dives into the whys and whats of Sometimes the Girl (did you know that almost every location in the book is a real place in very real Amherst, Massachusetts?), as well writing in general and hot gossip from Year Two of the Great Meadow Experiment. Who’s returning, who’s new, will Baby Dog ever get sick of standing in the middle and eating grass? Anyway, join us—I promise it will be…something.

Reviews? Allow me to present them!

Kirkus (starred review): “Mason-Black’s prose sparkles with poetic beauty as Holi engages in introspective musings about collective mourning and how individual healing is possible only in community… Beautifully written and powerfully uplifting.”

Booklist: “Mason-Black’s writing, expressed through Holi’s first-person narration, is original and striking in its depth, putting a thoughtful spotlight on Holi and the people around her. An appealing and engrossing work.”

Foreword Reviews (starred review): “Sometimes the Girl is a touching coming-of-age novel about healing and connection. Holi’s story models radical empathy, and its conclusion acknowledges that language is the only tool that may bridge the gap between people who seek to understand each other.”

And lists?

May 2025 Reads for the Rest of Us—Ms. Magazine

“Little does Holi know how much her life will change with Elsie in this powerful, lyrical story that honors creativity, queerness, healing and intergenerational relationships.”

20 Best May Books for Young Readers—Kirkus

Hot of the Press, May 2025—The Children’s Book Council

Shall we round it out with a guest post at the Teen Librarian Toolbox?

The Big Why: The Complications of Creativity and Sometimes the Girl

Coming soon: some exciting news! Stay tuned! In the meantime, if you need a copy, try Bookshop.org , Lerner Books , and, of course, your favorite local bookstore.

Stopping by to add a few new things here. First, an interview with me on the Lerner Blog. And second, another interview with me, this time at Forward Reviews. And third? Yet another interview, this time at Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb! I do love interviews (that’s actually true! they’re fun!)!

Be well, be brave, be open to wonder, dear ones!

May 7, 2025

March 3, 2025 (Take Two)

Howdy

Hello!

If you’re a longtime reader of Cosmic Driftwood, TA-DA! I’m still here and so are you! Perfect! (Too many exclamation points? Or okay?)

If you’re here for the first time, I’m so glad you found your way!

In either case, allow me some housekeeping. I’m Jen Mason-Black, author of a baker’s dozen of published short stories and the novels Devil and the Bluebird (Abrams/Amulet, 2016) and Sometimes the Girl (Lerner, Carolrhoda Lab, May 6, 2025).

This blog has been my online sanctuary since 2013. It’s been quiet for twoish years because my life was knocked off course for a bit, and then I had a newsletter, and then the newsletter platform shut down and then the country…things, the real answer is just, as always, things happened, big and small. Here we are now, though, and things are somewhat changed at Cosmic Driftwood, but mostly the same.

Changed how? Well, now you need to subscribe. With money? No, no money involved. Then why? Because I’m tired of an endless stream of spam, scams and AI. My goal is pure human interaction. Subscription is the route I’ve taken to help with that goal. So, subscribe and have access to the whole archive and get new posts in your email as soon as they go up. I’ll make briefer public posts from time to time that will cover writing news. For example, a new book (hold tight, intro to Sometimes the Girl coming soon) or a good review. If you’ve read all of this, though, you probably want to subscribe. It will be more fun than cold feet and hopefully better for your health.

You may wonder, how do I subscribe? Luckily, it’s really easy. So easy, in fact, that an endless stream of bots try. Find the subscribe button. Click. Follow the instructions. Relax and wait for approval. Once approved, open your email occasionally and read new posts. Be a person, live your life, do your best to love your people, do good deeds for yourself and others, hold fast during these hard hard times and don’t forget to accept what joy comes your way. (No subscription is needed for that part, but once I got started, I couldn’t stop.)

Love,

Me